Lakers’ 33-Game Winning Streak Meets the Bucks: January 9, 1972

Fifty years ago, one of the most dynamic games in NBA history was played between my team, the Milwaukee Bucks, and my future team, the Los Angeles Lakers.

Fifty years ago, on January 9, 1972, one of the most dynamic games in NBA history was played between my team, the Milwaukee Bucks, and my future team, the Los Angeles Lakers. The Lakers had already accomplished the extraordinary feat of a 33-game winning streak that made them an intimidating juggernaut of strength and skill. Lots of teams had bragged how they would end the streak, but all had failed. Now it was our turn to face them.

It was only my third year as a professional basketball player and I was determined to continue to give everything I had for the Bucks. The previous season, after acquiring the incomparable Oscar Robertson, we had gone on a 20-game winning streak, which was a new NBA record—until the Lakers’ phenomenal run shattered it. We had defeated the Lakers 4-1 in the Western Conference finals, And we had gone on to win the NBA championship by sweeping the Baltimore Bullets 4-0 in the finals. We were juggernauts, too.

However, we also remembered that we had lost to the Lakers early in their streak, 112-105. We’d been number 11 in their streak. So, while we weren’t intimidated by the Lakers, we were respectful.

This is a reader-supported newsletter. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. The best way to join the community and support my work is by taking out a paid subscription.

Still, there was some personal history going into this game. I would be facing one of the greatest players of all time, Wilt Chamberlain. Ten years earlier, Wilt had scored 100 points in a single game, a record that still holds today. He had been a hero of mine when I was still in grade school and had even taken me under his wing, inviting me to play cards at his house, taking me and my date out to his night club. He had fancy cars, lots of fawning friends, and was always in the company of beautiful women. To a young Black kid like me, he embodied what success might look like for me one day.

But by 1972, I wasn’t the same Black kid. My idea of success no longer looked like Wilt’s idea. It wasn’t based on flash and conspicuous wealth. I established that during the negotiations my first year in the NBA draft. The Nets and the Bucks both wanted me so I told them to make a one-time offer. There would be no going back and forth because at the time I felt that bidding wars degraded people. The Bucks made the better offer of $1.4 million, which I accepted. Immediately after, the Nets came back with an offer of $3.2 million, which I declined because I’d already given my word to the Bucks. I think the influence of my UCLA coach John Wooden, who always emphasized personal integrity over personal gain, had matured me away from my childhood fascination with Wilt’s glamorous lifestyle.

The difference in my path and Wilt’s was further highlighted the previous year. After winning the NBA championship, the U.S. State Department sent Bucks head coach Larry Costello, Oscar Robertson, and me on a basketball tour of Africa. I had already been studying Islam for several years before the trip but decided to announce by conversion to Islam, as well as my new name, on June 3, 1971 at the State Department. My teammates on the Bucks embraced the change with full support. So did a majority of Milwaukee fans.

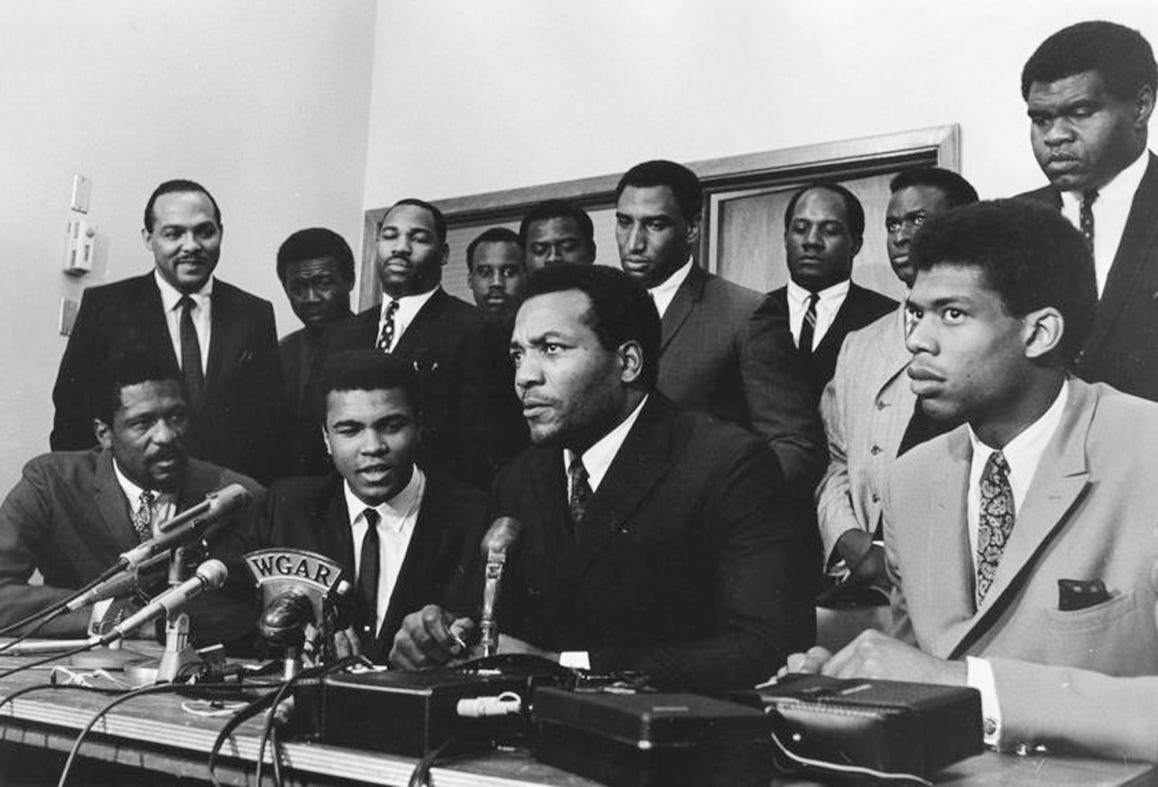

When the January 9 game took place, I had been Kareem Abdul-Jabbar for only six months. I had established myself as a tenacious player with a bunch of NBA records, but I had also established myself as a civil rights activist, having participated in the Cleveland Summit and having boycotted the 1968 Summer Olympics. I was not Wilt.